image copyright Céline Philippe, all rights reserved

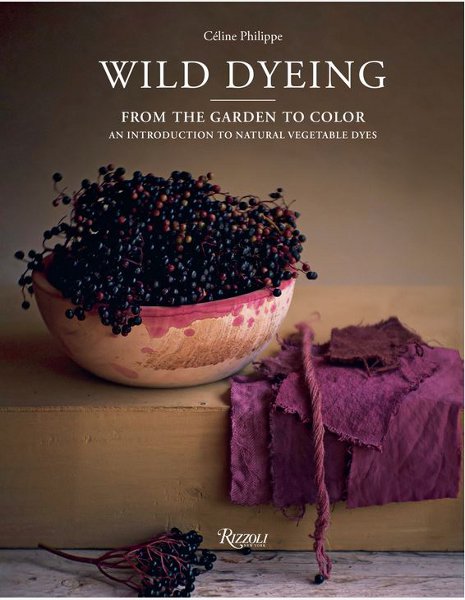

Wild Dyeing: From the Garden to Color

Céline Philippe, author and photographer

.

All content included on this site such as text, graphics and images is protected by U.S and international copyright law.

The compilation of all content on this site is the exclusive property of the site copyright holder.

Wild Dyeing: From Garden to Color

a book review

Sunday, 15 June 2025

Plants. What do we use them for. Food is a certainly important given. Buy in the shops. Grow in the garden. Forage in the wild. Anything else? Definitely! Herbs for healing. Fiber - just think of cotton and linen. Then, once woven into fabric, embellish with dyes. Which may also be made from plant stuff. Which is where "Wild Dyeing: From the Garden to Color" takes us.

image copyright Céline Philippe, all rights reserved

Wild Dyeing: From the Garden to Color

Céline Philippe, author and photographer

Céline Philippe is the creator of the Teinture Sauvage website with 24.2K subscribers dedicated to the artisanal practice of natural vegetable dyes using eco-friendly textiles and fibers. Her book was originally published in French in 2023 as Teinture sauvage: De la plante à la couleur. Initiation à la teinture végétale. Translated by Christiana Hills.

Have you ever accidentally spilled some tea? Unless you treated it right away, that left a stain on the fabric. Some spills are easier to remove than others. Done on purpose, that's dyeing. Dyeing depends on the dye stuff, on the fabric, on time and temperature.

Dyeing, like cooking, has some things to know before getting down to it. To begin with these necessary basics, Wild Dyeing focus on the fundamentals we need to know. These include the very basic - fibers for dyeing, animal origin such as wool and silk, or of plant origin such as cotton and flax (linen). While some dyes are substantive and do not fade, others require a mordent that will bond the dye to the fiber. While I am familiar with alum as a mordant it was fascinating to read about Philippe's research into plant based mordants. Pots, tools, a scale, etc. I didn't see a suggestion for keeping a different set of pots for dyeing, separate from those used for cooking food.

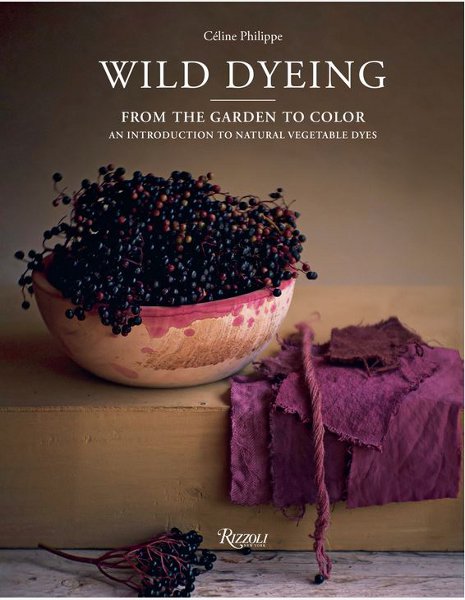

image copyright Céline Philippe, all rights reserved

One of the pleasingly graceful images, here introducing A Few Fundamentals to Know Before Getting Started.

Mordants, mineral based alum versus plant based mordants. Plants such as rhubarb which are rich in oxalic acid. Woods, bark, and tree galls high in tanins. As well as their common names many plants have usefully also been given their Latin name. For wild collected dye plants, she suggests that it is preferable to use those that are common, particularly any that are considered invasive as collecting them will not harm biodiversity. There is careful explanation of decoction, maceration, or fermentation to extract dye. Some language is emotive, saying that "Wool fears water that is too alkaline." Wool may react poorly but does it really have feelings? This section finishes with a useful two page summary spread of steps and actions essential to the dyeing process.

While there is no index, the front matter has a useful table of contents which allows the reader to easily reach the chapters and specific plants contained within.

Next, indigo. This familiar color is a magical one, but not the easiest to manage. An indigo dye vat has very particular techniques. There are options for extracting the colorant. Lists of equipment, materials, techniques. And tips for maintaining an indigo dye vat. She suggests starting with plant fibers as wool does not like bases, which roughen the wool. Only dye wool when pH has decreased, and pH 9 would be ideal. That may be, but I am puzzled because pH is a logarithmic scale where pH 7 is neutral. Lower numbers are acid, higher numbers are alkaline, and pH 9 is 100 times as alkaline as pH 7.

image copyright Céline Philippe, all rights reserved

Part 2 takes us on a Quest for Colors: Recipes and Inspirations. Four - let's call them "chapters" - each offer five or six possibilities from cultivated plants in the flower garden to vegetable plants in kitchen, wild plants along (sunny) paths and trees and shrubs in the shade of forest and hedges.

Each section opens with a full page image and an introductory paragraph. Then, each individual plant has a four page unit that opens with a full page image, a facing page that briefly lists important details: what part of the plant is used, when to harvest, suggested quantity, color range produced, and types of fibers to be dyed and mordant.

Let's examine one of the flower garden possibilities, which begins with sulfur cosmos. More information is given about the plant, how to sow, grow, harvest. Turn the page for Recipe, and facing page with four images, which show (clockwise from top left) a container of freshly harvested flowers, dyed fabric and fiber, a dye pot, and skeins of dyed fiber. Note: some plants are given just a full page rather than a four pac.

Identification of images for specific plants such as madder roots is good.

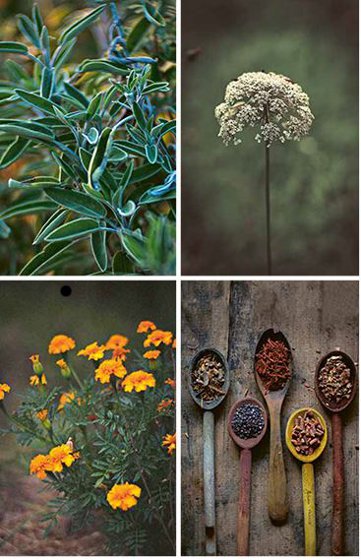

image copyright Céline Philippe, all rights reserved

It can be somewhat hit-or-miss. For example Page 23

top left is plant with silvery green leaves, next to image of ? Queen Anne's lace. Perhaps.

bottom left image is of French marigolds. On right 5 wooden spoons with bits and pieces.

Identifications, please.

Moving on. In the kitchen: vegetable plants are suggested as the first color resource as it is readily available to everyone whether they have a garden or not. I would venture that now avocados have become so expensive that if there's more that might be used, so much the better. Make your guacamole or avocado toast but save the peels and pits to use as a source for pink dye. Or onion skins. It is the rhizome of turmeric that provides the dye material. I don't recall seeing turmeric rhizomes offered for sale but the dried ground powder certainly is. Lacto-fermented beets - it is the liquid that will be used for dyeing; you eat the beets. And by the way, beets provide a natural food colorant known as beet red or E162, which is used commercially in hard candies, salad dressings, ready-made frostings, cake mixes, and gelatin desserts.

UPDATE I was in a supermarket on Friday, 20 June 2025

And what did I see but small packages of turmeric roots.

My error. Fresh turmeric is available. If my math is right,

a pound of turmeric roots would dye under 3 ounces of fiber.

The opening paragraph for Along the Paths: Wild Plants makes the good point that "Plant-based dyeing can help you discover the fabulous resources of these wild plants." because, as was said by botanist Gérad Ducef, "a weed is only a plant whose usefulness is unknown." That comment is even older, attributed to Ralph Waldo Emerson in his essay "The Fortune of the Republic", which was published in 1878. The plants discussed include goldenrod, hypericum, calluna, bitter dock and miscellaneous "white wildflowers" such as yarrow, chamomile, wild carrot. Options and possibilities: Several species of goldenrod, native to North America, have naturalized and become invasive in various parts of Europe, making it a good choice for wild dyeing both here in the United States and abroad. Likewise, Scotch heather, Calluna vulgaris, has naturalized in several parts of the United States.

At the Spinnery, her yarn shop in town, my friend Betty demonstrated

dyeing yarn with native plants that grow along the Delaware River.

Here she is lifting a skein of goldenrod dyed yarn out of its dye bath.

In the Shade of Forests and Hedges: Trees and Shrubs explores the uses of tree leaves, walnut husks, birch bark and harlequin glory bower, Clerodendrum trichotomum berries. It would have been well if these plants were discussed with Gérad Ducef, who is mentioned in a few places in this book. Where hardy, harlequin glory bower is considered invasive in the United States. Birch bark needs to be carefully collected to avoid damaging if not killing the tree. The walnut mentioned is Juglans regia, the common or English walnut. It would have been useful to include a sentence about J. nigra, native to central and eastern North America. A Wikipedia entry notes that "Black walnut drupes contain juglone (5-hydroxy-1,4-naphthoquinone), plumbagin (yellow quinone pigments), and tannin. These compounds cause walnuts to stain cars, sidewalks, porches, and patios, in addition to the hands of anyone attempting to shell them."

A translation should do more than merely word for word. It would be improved by localization, adjusting the text for regional / geographical differences.

Wild Dyeing: From the Garden to Color has an eco-friendly approach that goes beyond merely dyeing using plant sources—roots, berries, bark, leaves, and wood. Céline Philippe takes her readers and aspiring craft workers out into the natural world to explore. And enjoy. She hopes that "the special alchemy of plant color will give you a dose of wonder."

Wild Dyeing: From the Garden to Color

Céline Philippe, author and photographer

First published in the United States in 2025

by Rizzoli International Publications, Inc.

originally published in French in 2023 by Gallimard

ISBN 978-0-8478-4546-0

hardbound, $35.00

A review copy of this book was provided by the publisher

Back to June

Back to Book Reviews, 2025 edition

Back to the main Diary Page